Grace Parsons School of Design Southwest School of Art

| |

| Former proper noun | Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts |

|---|---|

| Type | Private art school |

| Established | 1826 (1826) |

| Affiliation | AICAD |

| Endowment | $92.ix meg (2020)[1] |

| President | Samuel Hoi |

| Academic staff | 178 full-time 433 part-time |

| Students | 2,128[2] |

| Undergraduates | 1,824 |

| Postgraduates | 379 |

| Location | Baltimore Maryland Usa |

| Campus | Urban, 1.five miles (2.iv km)[ clarification needed ] |

| Colors | Blue & Yellow (traditionally) Light-green & Chocolate-brown (more recently) |

| Website | www |

The Maryland Constitute College of Art (MICA) is a private fine art and pattern college in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1826 equally the Maryland Constitute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts,[iii] making it i of the oldest art colleges in the United States.

MICA is a member of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD), a consortium of 36 leading Us art schools, besides as the National Association of Schools of Fine art and Design (NASAD). The college hosts pre-higher, mail service-baccalaureate, continuing studies, Main of Fine Arts, and Bachelor of Fine Arts programs, as well as immature peoples' studio art classes.

History [edit]

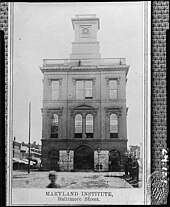

"The Maryland Institute", to a higher place the old "Centre Market place" on Market Place betwixt East Baltimore Street and Water Street, due east of South Frederick Street and west of the Jones Falls stream, home of M.I., 1851–1904

Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts [edit]

The Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts was established by prominent citizens of Baltimore, such equally Fielding Lucas Jr. (founder of Lucas Brothers - office supply company), John H. B. Latrobe (lawyer, artist, writer, civic leader), Hezekiah Niles (founder of national newspaper Niles Weekly Register) and Thomas Kelso.[3]

Other leaders and officers in that first decade were William Stewart (president), George Warner, and Fielding Lucas Jr. (vice presidents), John Mowton (recording secretary), Dr. William Howard (corresponding secretary), also equally James H. Clarke and D.P. McCoy (managers), Solomon Etting (local merchant/pol), Benjamin C. Howard, William Hubbard, William Meeter, William Roney, William F. Small, S.D. Walker, John D. Craig, Jacob Deems, William H. Freeman, Moses Manus, William Krebs, Robert Cary Long, Jr. (builder), Peter Leary, James Mosher, Henry Payson (founder of First Unitarian Church), P. Chiliad. Stapleton, James Sykes and P. B. Williams. The General Assembly of Maryland incorporated the Found in 1826, and starting in November of that year (Tuesday, November 7, 1826), exhibitions of articles of American manufacture were held in the "Concert Hall" on South Charles Street. A course of lectures on subjects connected with the mechanic arts was inaugurated, and a library of works on mechanics and the sciences was begun.

The school operated for a decade at "The Athenaeum" (the kickoff of two structures to bear that name, a landmark for educational, social, cultural, civic and political affairs) at the southwest corner of Due east Lexington and St. Paul Streets facing the second Baltimore Metropolis/County Courthouse between North Calvert and St. Paul Streets. This outset Archives was destroyed by fire on February seven, 1835 along with all of its property and records. The fire was acquired past a bank riot due to the financial panic following the collapse of several Baltimore banks.[4]

In November 1847, Benjamin South. Benson and threescore-nine others (including many of the original founders of the sometime Institute), issued a phone call for a meeting of those favorable to the formation of a mechanics' plant, which resulted in the reopening of the Institute on January 12, 1848.[three]

The first annual exhibition was held at "Washington Hall" in October 1848, followed past 2 more. The 1848 officers were John A. Rodgers – president, Adam Denmead – first vice president, James Milholland – second vice president, John B. Easter – recording secretary, and Samuel Boyd – treasurer. The Constitute was reincorporated by the land legislature at their December session in 1849 and was endowed by an annual cribbing from the State of Maryland of five hundred dollars. In 1849, the Lath of Managers extended the usefulness and broadened the appeal of its programs to ordinary citizens by opening a School of Design and an additional Nighttime Schoolhouse of Pattern was extended ii years later in the new hall and building, nether William Minifie (from the Kinesthesia of the old Central High School of Baltimore) as principal of the reorganized Establish. Classes resumed in rented infinite over the downtown Baltimore branch of the U.S. Post Office Section in the "Merchants Substitution".[5]

The City Council in 1850 passed an ordinance granting the Constitute permission to erect a new building over a reconstructed "Centre Market", laying the cornerstone on March 13, 1851, with John H. B. Latrobe,[4] and son of national builder Benjamin Henry Latrobe, (1764–1820).

In 1851, the Institute moved to its own building, congenital in a higher place the old Centre Market on Marketplace (formerly Harrison Street) between East Baltimore Street (to the north) and Water Street (to the s) alongside the western shore of the Jones Falls. Centre Market connected to be known in the urban center as "Marsh Market place" afterward the former Harrison's Marsh from colonial times. The building covered an entire cake and had two stories built on a series of brick arches higher up the market, with 2 clock towers at each end. The second flooring with the Establish, housed classrooms, offices, shops and studios and 1 of the largest assembly halls/auditorium in the state.

During this period the Institute added a School of Chemistry, cheers in part to a bequest from philanthropist George Peabody, (1795–1869), (for which the Peabody Institute and George Peabody Library is named) and B.& O. Railroad President Thomas Swann, along with a School of Music.[5] Nighttime classes for Design are added for men who work during the day, only would similar training in Compages and Engineering science at night. In 1854, a Day School of Pattern opened for women—one of the beginning U.s. arts programs for women. In 1860, the Day Schoolhouse for men opened, and in 1870, the Day school became co-ed.[5]

The Maryland Institute, after the 1904 Burn

For 79 years the Institute remained in the location above the Centre Marketplace, and its "Great Hall", large enough to adapt six,000, attracted many famous speakers and lecturers. Information technology hosted events and shows related to the Arts, and as one of Baltimore'southward largest halls, it hosted of import events to the city and the region. In 1852, it hosted both of the National political conventions to nominate presidential candidates Winfield Scott and his opponent Franklin Pierce (who was subsequently elected 14th President of the The states).[5]

During the American Civil War, the Institute served briefly as an armory for the Union and a hospital for soldiers wounded at the Battle of Antietam.[5] On Apr 18, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln gave his famous voice communication known equally the "Baltimore Address" (or "Liberty Speech") during a "Sanitary Fair" held in the Cracking Hall to do good Union soldiers and families.

On February 7–viii, 1904, the Centre Market and the Maryland Establish burned down along with ane,500 other buildings in downtown Baltimore during the Peachy Baltimore Fire.[v] Temporarily, classes moved to spaces above other covered municipal markets in the city, while construction was ongoing in two locations. Michael Jenkins donated the future site of the "Main Edifice" on Mount Royal Artery near the new Bolton Hill neighborhood in the northwest, which opened in 1908. It was to house the School of Art and Blueprint, and the Urban center of Baltimore offered the one-time site and funding to rebuild the Centre Market as a location for the Drafting school and "mechanical arts".[half dozen]

Upon opening, the Primary building had spaces for pottery, metal working, wood carving, gratuitous-manus drafting and textile pattern, too every bit a library, galleries and exhibition rooms. The galleries and exhibition rooms were of import, because at the time of construction, Baltimore had no public art museum (institutions such as the Walters Art Gallery were not founded and opened for regular public viewing until 1909 and acquired by the city in 1934, and the Baltimore Museum of Art, in 1914).

In 1923, the Institute's galleries hosted the first known public showing of Henri Matisse's piece of work in the United States, brought from Europe by sisters Claribel and Etta Cone.[6] In 1928, the new Heart Market edifice, now known as "The Market Identify" building, offered a course in Helmsmanship theory and drafting following the bully excitement and increase in interest in the industry following Charles Lindbergh's flight over the Atlantic Ocean to Paris.

Maryland Institute, Higher of Art [edit]

The Plant legally changed its name to the "Maryland Institute, College of Art" in 1959, and the "Market place Identify Building" was razed to make room for the extension south of the Jones Falls Throughway (Interstate 83).[6] The consolidation of MICA to the Mount Royal campus was furthered by the purchase of the Mountain Purple Station, a former Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) train station, in 1964. In 1968, MICA was forced to close due to the Baltimore riot of 1968, which broke out two days after the April 4 bump-off of Martin Luther Male monarch Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee.

From 1972–1975, MICA was graced with the presence of artists and critics of the catamenia, including composer John Cage, poet Allen Ginsberg, lensman Walker Evans, master printer Kenneth E. Tyler, painter Elaine de Kooning and fine art critic Clement Greenberg.[7]

In the following years, MICA expanded along Mount Royal Avenue, adding the "Fox Building" in 1978, the "College Middle" (now the "Art Tech Centre") in 1986, a renovation of the "Principal Edifice" in 1990, "The Commons" (added 1992), "Bunting Center" (1998), the "Meyerhoff Business firm" (2002), the "Brown Middle" (2003), the "Studio Center" (2007) and "The Gateway" (2008). During that time, the College focused on increased interaction with the international art world—offer written report away programs and residences in numerous countries around the world.

The schoolhouse'south logo was redesigned in 2007 by Abbott Miller of Pentagram and is said to be a "visual reference to the architecture" found at the 1907 Principal Edifice and 2003 Dark-brown Center.[8]

Academics [edit]

MICA offers various undergraduate caste, graduate degrees and certificates including B.F.A., Chiliad.A., 1000.A.T., M.B.A., M.F.A., Yard.P.S.[9] [10] [11] Some of the degree programs are partially online or fully online.[nine] The school has accreditation from Eye States Committee on Higher Didactics (MSCHE) since 1967, and National Clan of Schools of Art and Design (NASAD) since 1948.[2] [ix]

In the Fall 2017 term, at that place were 433 part-time faculty and 178 total-time faculty, with an 8 to 1 student-to-faculty ratio.[2]

Students and alumni [edit]

Pupil fine art exhibit, May 2012.

In Fall 2017, the total educatee enrollment was 2,128, with 1,824 undergraduate students and 379 graduate students hailing from beyond the US and foreign countries.[2] The pupil torso in Fall 2017 was 75% female and 25% male.[2] MICA has an acceptance rate of 62% in 2017.[12] [13]

86% of B.F.A. graduates who take jobs immediately later on graduation are working in art related fields; 23% of MICA's B.F.A. graduates pursue graduate written report immediately after graduation.[ commendation needed ]

From 2009-2017, 14 MICA graduates received Fulbright awards for study abroad and v students earned the Jacob Javits Fellowship for graduate study.[ citation needed ] Since 2003, 2 alumni have received the national Jack Kent Cooke Foundation Graduate Scholarship and three Jack Kent Cooke Foundation scholars chose to report at MICA. Additionally, four alumni were awarded Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grants.[ commendation needed ]

Facilities [edit]

MICA's campus is a mixture of buildings from unlike periods of Baltimore's development.

Primary building [edit]

The Main Edifice houses painting and cartoon studios, undergraduate photography department, foundation section, two departmental galleries, undergraduate admissions and the President's Function.

Construction began on a new campus in Bolton Hill when its Eye Market place building was destroyed. Construction was completed in 1908.[14] The State of Maryland, the Carnegie Foundation, and local benefactors contributed funds to build it. Michael Jenkins donated the land, stipulating that the new building non disharmonism with the nearby Gothic Revival Corpus Christi Church building.[14] The Primary Building was the starting time to be designed by New York-based architects Pell & Corbett, who were awarded the contract when they won a $500 design competition sponsored by the New York Clan of Independent Architects. Otto Fuchs designed the interior studio plans. The compages was intended to evoke a feeling of the Grand Culvert of Venice, c. 1400. The exterior marble is carved from "Beaver Dam" marble, excavated from the Baltimore Canton quarry nigh Cockeysville, Maryland. It is the same marble used to build the Washington Monument in Baltimore designed by Robert Mills, and function of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C.[5]

| Mount Royal Station | |

| U.S. National Register of Celebrated Places | |

| U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

The former B&O station, now the Maryland Plant Higher of Art, in 2009 | |

| Location | 1400 Cathedral Street, Baltimore, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°eighteen′twenty″N 76°37′14″W / 39.30556°N 76.62056°Westward / 39.30556; -76.62056 Coordinates: 39°xviii′20″Northward 76°37′xiv″West / 39.30556°Northward 76.62056°W / 39.30556; -76.62056 |

| Built | 1896 |

| Builder | Baldwin, E. Francis; Pennington, Josias |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| NRHP referenceNo. | 73002191 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 18, 1973[15] |

| Designated NHL | December viii, 1976[16] |

Architectural features include the master entrance, offering a large marble staircase, stained-glass skylight and the names of Renaissance masters surrounding the entrance to the second floor. The exterior of the northeast façade features four stone memorial medallions: one for the city, 1 for the land and two others honoring Institute benefactors Andrew Carnegie and Michael Jenkins.[14] Throughout the Main Edifice plaster replicas of Greek and Roman statues offering students report targets for their Foundation year.

In 1908, the New York Association of Independent Architects awarded the building a gilt key, the highest honour in architecture at the time.

From 1990-1992, the building underwent a $five.one million renovation under the management of the Grieves, Worrell, Wright & O'Hatnick, Inc (GWWO) architectural firm. The renovation upgraded the building's facilities and created additional bookish and office space while retaining much of the original blueprint and décor.

Mount Royal Station [edit]

The Mountain Royal Station houses the undergraduate departments of fiber and interdisciplinary sculpture, 3D classrooms, and the Rinehart School of Sculpture, as well as senior studios.[17] The railroad tracks underneath the railroad train shed remain active equally CSX Transportation's freight mainline to New York City.

Built in 1896, the Mount Royal Station (now known as The Station Building) was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's showcase passenger station until it ceased operations in 1961.[17] MICA purchased the edifice in 1964 and renovated it in 1966 nether the direction of architect Richard Donkervoet, retaining as much of the building'south exterior and interior every bit possible, including vaulted ceilings, columns and mosaic flooring.[xviii] Margaret Mead, in a lecture given at the Station, commented that the renovation "is perhaps the most magnificent example in the Western Globe of something being fabricated into something else".[18]

On December 8, 1976, the Station was added to the annals of National Historic Landmarks, granting it full protection every bit an historic site.[nineteen] The Mount Royal Station's gable-roofed railroad train shed, 1 of the country's last remaining such structures,[19] was renovated in 1985. Between 2005–2007, MICA accomplished a ii-phased, $6.iii million renovation by the architectural firm Grieves, Worrall, Wright & O'Hatnick, Inc. (GWWO).[17]

Dolphin Building [edit]

The Dolphin Edifice at 100 Dolphin Street formerly housed MICA's Printmaking section and Book Arts and Printmaking concentrations, equally well every bit the independent Dolphin Press. It had 15,000 square anxiety (i,400 g2) of working space divided into three floors. In 2016, MICA demolished the Dolphin Edifice in grooming of a 5 story/25,000 square feet construction, designed by Baltimore architectural firm GWWO.[20] [21] The edifice reopened in September 2017, and is at present home to the Interactive Arts, Game Design, Product Design, and Architectural Design departments.[20] [22]

Bunting Center [edit]

Bunting Center houses Liberal Arts departments (art history and language, literature, and culture), the campus Writing Center, academic advising and the registrar. Bunting Middle also houses a eating house, Coffee Corner. The outset floor and basement level house the Decker Library, which includes a collection of over 600 art books in its Special Collections expanse. Students are immune to view any Special Collections item by requesting it from library staff. The library too includes an oversized Folio section and a wide collection of video and film materials, including DVD and Blu-ray. It hosts display cases for monthly exhibits, a private Screening Room for viewing films and holding meetings, and a classroom for educational activity.[23] Bunting Middle contains the Pinkard Gallery and Student Space Gallery.

The acquisition and renovation of Bunting Center increased MICA'south academic space by 20% when it opened in 1998. It was named for trustee George Bunting, who was besides instrumental in the development of the Flim-flam Edifice, among other projects.

The Bunting Heart received the One thousand Blueprint Award and Accolade Award from AIA Baltimore in 1998. In 2007, architect Steve Ziger headed the building's $five.v one thousand thousand renovation, seeking to create "a real sense of neighborhood" for the college.

Firehouse [edit]

The Firehouse hosts the College's operations and facilities direction department. The edifice has seven,224 square feet (671.1 one thousandii) of space. MICA purchased a historic Firehouse along North Avenue in 2001 and renovated the building in 2003. As part of the redevelopment agreement, MICA maintained the station's front façade in accordance with Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation standards. The renovation architect was Cho Benn Holback + Associates, Inc. Kajima Construction Services was the contractor. The Firehouse won an award from the Baltimore Heritage Foundation for preservation in 2004.

Play a trick on Building [edit]

The edifice houses Decker Gallery, Café Doris, Meyerhoff Gallery, the Center for Fine art Education, the Partition of Standing Studies, besides as Ceramics, Illustration, Ecology Design, GFA, Drawing and Painting departments, the woodshop, the nature library, and Graphic Blueprint MA (formerly Graphic Pattern Post-Baccalaureate). The Trick Edifice offers more than 60,000 square feet (five,600 m2) of usable space.

Built in 1915 as the Cannon Shoe Factory, the Fox Building was purchased in 1976. Afterward 2 years of planning by architects Ayers/Saint/Gross, work began in 1979 and the newly renovated edifice opened in 1980. This renovation retained about of the warehouse character of the building, including exposed ductwork and framing and the original exterior—The renovations cost $ii.5 meg, and the building was named for architect Charles J. Fox, a 1965 graduate of MICA whose family unit contributed over $i.5 million of the renovation cost. Afterward the conversion, the Mount Purple Improvement Clan granted MICA an Award of Merit for its contribution to the community.

In 2005, a second renovation added another gallery and cafe.

Banking company Building (Studio Center) [edit]

The 120,000-square-foot (xi,000 k2) building houses the mail-baccalaureate document program, Hoffberger School of Painting, The Mount Imperial School of Art, the Graduate Photographic and Electronic Media program, and Senior pupil studios. Although the official name is The Studio Center, many students know it equally The Bank Building.

MICA purchased the former Jos. A. Bank sewing constitute on North Avenue in Baronial 2000. The all-brick building dates to the early 20th century and was home to Morgan Millwork for most of the century.

Brown Center [edit]

The Brown Center houses MICA's digital art and design programs, equally well every bit the 525-seat Falvey Hall, which, in add-on to hosting school-related functions, has also played host to events similar the Maryland Film Festival and National Portfolio Day. It houses the Video, Animation, and BFA and MFA Graphic Blueprint departments. It too has an art gallery, a secondary hall for lectures ("Brown 320"), and a "Black-Box" area for Interactive Media installations.

The starting time newly synthetic academic building for the College in almost a hundred years, Chocolate-brown Center was defended on October 17, 2003 and became fully operational in Jan 2004.[24] Information technology was bolstered past a $six 1000000 gift from Eddie and Sylvia Brown, the largest gift ever received past the Institute. The edifice was designed by architect Charles Brickbauer and Ziger/Snead.[25]

The 61,410-square-foot (v,705 k2), five-story contemporary structure garnered acclaim as an architectural landmark. Awards accept included the AIABaltimore 2004 G Design Award, AIA Maryland 2004 Award Award of Excellence, regional award of merit in 2004 in the International Illumination Blueprint Award competition, and several awards for excellence in structure. In addition, MICA President Fred Lazarus traveled to Italy in June 2006 to receive the Dedalo Minosse International Prize for Chocolate-brown Center. Brown Center was the only American project among the finalists.

Additional facilities [edit]

Boosted buildings making upward MICA's campus include the Maryland Plant College of Art store (known simply as "The MICA Shop") at 1501 W. Mount Regal Ave. selling art supplies and books, and official MICA merchandise.[26]

Student housing [edit]

The Meyerhoff and The Gateway buildings increased MICA educatee housing 90% between 2002 and 2009, allowing more students to stay on campus.[ citation needed ]

Founder's Greenish [edit]

Founder's Green is a iii-edifice, four-story student apartment complex. Among the starting time student residences to be constructed on the flat-living model, it houses approximately 500 students.[27] When MICA proposed purchasing a lot on McMechen Street that had been vacant for more than xxx years, to build student housing, and the Bolton Hill neighborhood approved the purchase and donated $50,000. Built in 1991, and previously named "The Eatables".[27] In 2012, the edifice was renamed and renovated into the flat-style by architecture house, Ayers Saint Gross.[27]

Meyerhoff Business firm [edit]

Meyerhoff House is a residence for Sophomore, Inferior and Senior students. The edifice includes the College's main dining facility, student life center and recreational civilities. Originally built as the Infirmary for the Women of Maryland, the building was used as nursing home for some time until it closed in 1994. The building was vacant for 7 years until MICA purchased it in Jan 2001.[28]

The Gateway [edit]

The Gateway includes apartments to accommodate 217 pupil residents, a translucent studio tower, a multi-use performance space, the Higher'due south largest student exhibition gallery, and a new home for the Joseph Meyerhoff Eye for Career Evolution. The Gateway is located at the intersection of Mount Royal and North avenues, alongside the Jones Falls Expressway (I-83). Construction began on The Gateway in October 2006 and completed in August 2008. It was designed past RTKL Associates Inc.[29] In August 2008, the first students moved into the Gateway.

Notable alumni [edit]

Notable erstwhile students of the Maryland Plant College of Art include the following individuals, listed past field of work:

Academia [edit]

- Earl Hofmann (B.F.A. 1953), painter, educator[thirty]

- Marking Milloff (M.F.A.), multidisciplinary creative person and educator at Rhode Island School of Blueprint[31]

- Andrew Cornell Robinson (B.F.A.1991), professor at Parsons The New School for Design, painter, printmaker, and sculptor[32]

- Dorothy Cavalier Yanik (Painting M.F.A. 1975) professor at Carnegie Mellon University and diverse other schools

Actors [edit]

- Tamara Dobson (Fashion Illustration B.F.A. 1970), actress in Cleopatra Jones and mode model.[33]

- Abbi Jacobson (General Fine Arts B.F.A. 2006), comedian, writer, extra, and illustrator known for her work on the TV series Broad City [34]

- Colby Keller (Thou.F.A. 2007), pornographic film role player, visual artist, and blogger

- Susan Lowe (B.F.A.) actress and i of the Dreamlanders

- Maelcum Soul, (Painting B.F.A.) actress and painter

Architects [edit]

- Richard Armiger (1970), architectural model maker

- Wright Butler (1891), architect

- John Jacob Zink (B.F.A. 1904), builder of flick houses[35]

Business [edit]

- Heather Day (B.F.A. 2012), abstract painter and entrepreneur of the culinary-art startup, Studio Table[36]

- Deana Haggag (Curatorial Practise M.F.A. 2013), President and CEO of the national arts funding organisation U.s.a. Artists

- Dana Veraldi (Photography B.F.A. 2007), designer, artist, and entrepreneur known for her t-shirt line[37]

Designers [edit]

- Cheryl D. Miller (B.F.A. 1974), AIGA Medalist 2021

- Zach Richter (B.F.A. 2007), creative managing director of digital and VR experiences, designer

Picture [edit]

- John Carter (B.F.A. 1992), film director and conceptual artist

Musicians [edit]

- David Byrne (never graduated, attended 1971–1972), vocalizer, fellow member of Talking Heads ring

- Frances Quinlan (Painting B.F.A. 2008) in the indie band, Hop Forth[38]

Fine Arts [edit]

Illustrators [edit]

- Jeremy Caniglia (One thousand.F.A. 1995), illustrator of volume cover art for fantasy and horror genres

- Jennifer Daniel (illustrator) (B.F.A. 2000), emoji subcommittee chair

- ND Stevenson (B.F.A. 2013), illustrator and cartoonist

- Babs Tarr (B.F.A. 2010), illustrator

- Annie Wu (B.F.A. 2010), illustrator and comic book artist

Multimedia, mixed media and installation [edit]

- Jim Condron, (M.F.A. 2004), painter and mixed media artist[39]

- Michael Corris (M.F.A. 1972), conceptual artist and writer on art.

- Jane Frank (B.F.A. 1935), painter, sculptor, mixed media artist, and textile creative person

- Gaia (B.F.A. 2011), street muralist and artist.[40]

- Jeff Koons (B.F.A. 1976), sculptor and painter

- Jenni Lukac, contemporary artist

- Jimmy Joe Roche (M.F.A. 2008), visual artist and underground filmmaker

- Shinique Smith (Full general Fine Art B.F.A.1992, Mount Royal School Of Art Chiliad.F.A. 2003), painter, sculptor, and installation artist[41]

- Jen Stark (2005), paper sculptor, drawer, and animator

- St. Clair Wright (1932), preservationist and gardener

Painters [edit]

- Dhruvi Acharya (Painting M.F.A., 1998) [42]

- Kamrooz Aram (B.F.A. 2001), painter.[43]

- Donald Baechler (B.F.A. 1977), painter[44]

- Angie Elizabeth Brooksby (1988), painter

- Larry Poncho Dark-brown (1984), painter and sculptor

- Jeremy Caniglia (1995), figurative painter

- Lesley Dill (1980), contemporary artist

- William Downs, (2003), painter

- Danielle Eckhardt, painter

- John Ennis (1976), painter

- Brock Enright (1998), painter

- Joan Erbe (1950), painter, sculptor

- Amir H. Fallah (built-in 1979, Painting B.F.A. 2002), painter and magazine publisher

- Joshua Field (1996), painter

- Lee Gatch, painter

- Gladys Goldstein, painter

- Elaine Hamilton (1945), painter and muralist

- Douglas Hoffman (1968), painter and printmaker

- Earl Hofmann (1953), painter and educator[xxx]

- Kika Karadi (1997), painter

- Morris Louis (1933), painter

- Ted Mineo (Painting B.F.A. 2002), painter[45]

- Karin Olah (1999), contemporary painter, collage, and cobweb artist[46]

- Selma L. Oppenheimer, painter

- Amalie Rothschild (1934) painter and sculptor

- Shelby Shackelford (1921), painter, printmaker, illustrator

- Amy Sherald (M.F.A. 2004), painter[47]

- Lee Woodward Zeigler (1885), muralist and illustrator

Photographers [edit]

- Joan Cassis (1974), photographer[48]

- Linda Mean solar day Clark (B.F.A. 1994), photographer

- Lola Flash (1981), photographer

- Marilyn Nance (1996), photographer

Sculptors [edit]

- Nina Akamu (B.F.A. 1977), sculptor

- Matt Johnson (2000), sculptor

- Ernest Keyser, sculptor

- Gwen Lux (attended 1926–1927), sculptor and Guggenheim young man in 1933 for Fine Arts[49]

- James Earl Reid (1942–2021), sculptor[50]

- William Henry Rinehart, sculptor

- Jacolby Satterwhite (2008,) video artist

- Hans Schuler (1899), sculptor

- Joyce J. Scott (1970), sculptor, beadworker

Notable faculty [edit]

- Timothy App, painter

- Laurence Arcadias, animator

- Joe Cardarelli, poet

- Norman Carlberg

- Jim Condron, painter, mixed media artist

- Gladys Goldstein, painter

- Grace Hartigan

- Earl Hofmann, painter

- Yumi Hogan, painter, First Lady of Maryland

- Nate Larson, photographer

- Ellen Lupton, graphic designer

- Raoul Middleman

- Salvatore Scarpitta, sculptor

- José Villarrubia, illustrator

- John Yau, poet

- Patrick O'Brien, illustrator

References [edit]

- ^ Every bit of June thirty, 2020. U.Southward. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market place Value and Modify in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Association of College and University Business organisation Officers and TIAA. February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "College Navigator - Maryland Institute College of Art". National Heart for Education Statistics (NCES). U.S. Department of Education. 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Vincent, John Martin (1889). The Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science. Johns Hopkins Academy Press. p. 63 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "MICA Historical Timeline". 2009. Archived from the original on June ten, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "1847-1878: Renewal and Expansion in the Industrial Age". 2009. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved Baronial 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c "1905-1960: A Fresh Offset—Rise of Mount Royal Campus". 2009. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved August xxx, 2009.

- ^ "1961-1977: Rapid Strides Forrad—Becoming a Higher". 2009. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Vozzella, Laura (April 1, 2007). "Brand-new logo, $75,000; MICA's explanation, priceless". The Baltimore Sunday . Retrieved Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Maryland Institute College of Art". Association of Contained Colleges of Fine art & Design (AICAD) . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Sweeney, Alexis (2002). "Maryland Institute College of Art". The Baltimore Sun . Retrieved Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ "Graduate Fine art & Design programs - Announcements". Fine art & Education. 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Maryland Institute College of Fine art". US News and Reports. 2017.

- ^ "Maryland Constitute College of Fine art". The Princeton Review College Rankings & Reviews . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Mary Ellen Hayward & Frank R. Shivers, Jr., ed. (2004). The Architecture of Baltimore. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Up. ISBN0-8018-7806-3.

- ^ "National Register Information Arrangement". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Apr 15, 2008.

- ^ "Mount Royal Station and Trainshed". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c Gunts, Edward (June twenty, 2005). "MICA station will go a makeover". The Baltimore Sun . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Gunts, Edward (August 29, 1996). "Mount Majestic Station turns 100 Preservation: The former pride of the B&O; became 1 of the country's start examples of adaptive reuse when Maryland Institute converted it for art space in the 1960s". The Baltimore Dominicus . Retrieved Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "National Annals Properties in Maryland". Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Gantz, Sarah (September 23, 2016). "MICA moves frontward with Dolphin Street sabotage and new building". The Baltimore Sun . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Gantz, Sarah. "MICA moves forward with Dolphin Street sabotage and new building". baltimoresun.com . Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ "Collaborative Past Design – Maryland Establish Higher of Fine art". mica.edu. November 7, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Fine art, Maryland Institute College of. "Decker Library - MICA". world wide web.mica.edu . Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "1978-Today: A Vital Strength for Change–Expanding the Role of Artists and Designers". Maryland Found College of Art. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ "Dark-brown Center". Architectural Tape. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Weigel, Brandon (March 16, 2018). "Jubilee Arts, #MadeInBaltimore to have office in MICA Shop 1000 opening". Baltimore Fishbowl . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Kilar, Steve (2013). "With modern dorm on Due north Ave., MICA creates residential hub for students". The Baltimore Lord's day . Retrieved Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ Gunts, Edward. "Maryland Institute buys former Women's Infirmary". Baltimore Sun . Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Mays, Vernon (February 10, 2009). "The Gateway, Maryland Institute College of Fine art". Architect Mag . Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ a b "Earl Francis Hofmann, realist painter, instructor". BaltimoreSun.com. October three, 1992. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "Mark Milloff". www.risd.edu . Retrieved January three, 2019.

- ^ "Andrew Cornell Robinson". Artspace . Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "Smart, Alpine and Beautiful, Tamara Dobson". African American Registry . Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Instance, Wesley (February 26, 2016). "'Broad City' star Abbi Jacobson talks seeing a Baltimore mugging on podcast". BaltimoreSun.com . Retrieved Jan 3, 2019.

- ^ "Zink, John Jacob (1886 - 1952) -- Philadelphia Architects and Buildings". www.philadelphiabuildings.org . Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Marina (July 22, 2015). "Inside the Vibrant Life of Painter Heather Solar day". 7x7 magazine.

- ^ Wellington, Elizabeth. "Celebrity T-shirt designer Dana Veraldi is coming to Philly". world wide web.philly.com . Retrieved Jan 3, 2019.

- ^ "Frances Quinlan, Stone and Whorl Painter". Newspaper. Feb 19, 2020. Retrieved Apr 2, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Tim (January 31, 2017). "Baltimore-based artist Jim Condron receives $30,000 Pollock-Krasner honour". The Baltimore Sunday. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Scharper, Julie (2014). "Open Walls, open up dialogue". The Baltimore Sunday . Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "A Conversation with Shinique Smith". MICA . Retrieved January four, 2019.

- ^ "Immature guns who represent the changing face of Republic of india". India Today. January 31, 2005.

- ^ "Kamrooz Aram: Lecture". VCUarts Department of Painting + Printmaking. August 29, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Abstract artist Donald Baechler '77 (painting)". MICA . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Apr 07, WM Issue # two: Ted Mineo, DEITCH PROJECTS". Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art . Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Nick (October 31, 2007). "VISUAL ARTS PREVIEW: Incantations in Thread". Charleston City Newspaper. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ McCauley, Mary Carole. "Equipped with new heart, Baltimore'due south Amy Sherald gains fame with surreal portraiture". baltimoresun.com . Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Hilson, Jr., Robert. "Joan Cassis, 43, photographer who combined film with pigment". Baltimore Sun . Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Gwen Lux". John Simon Guggenheim Foundation . Retrieved January four, 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Jacques (August 7, 2021). "Sculptor James Earl Reid, whose work addressed racism and social justice, dies". Baltimore Dominicus . Retrieved September 13, 2021.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Maryland Institute Higher of Art at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Maryland Institute Higher of Art at Wikimedia Eatables - Official website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maryland_Institute_College_of_Art

0 Response to "Grace Parsons School of Design Southwest School of Art"

Post a Comment